In 2014, The Wall Street Journal published a note asking: "Is Uber valued at $ 18.2 billion?" Even then, the legendary venture capitalist Bill Gurley softly objected to the author, NYU Stern professor Aswat Damodaran, writing that the amounts from the article in the future will differ from reality by twenty-five or more times. Gurley was right: Uber is already valued at more than $ 50 billion and occupies about 70% of the market. Damodaran's assumptions, by contrast, were fundamentally wrong.

Although Gurley did not say anything specific about the cost of Uber, he certainly expected that in the next five years it would increase by more than 192%. Of course, much has happened since then, in particular, disastrous for the company in 2017, when the scandals around Uber seemed endless. The startup lost the CEO and, even worse, allowed Lyft to develop - the main competitor, which at the beginning of that year was on the verge of bankruptcy. It is fair to say that without a large-scale competitor, Uber seemed a much more expensive company.

Uber critics made a mistake when they called this service an analog of a traditional taxi. However, this does not mean that people with the opposite opinion were completely right. The opposite of a traditional company does not have to be a technology company. Previously, we simply did not notice this, but a strict choice between a technological and a traditional approach is not optimal.

Why do Uber drivers suffer

In the summer, California passed Bill AB 5, which sets out the decision of the California Supreme Court to conduct a three-part test that determines whether the person is an independent contractor or employee (with all associated taxes that accompany this classification).

From the decision:

Using this test, the worker is fully considered an independent contractor, to whom the wage order does not apply only if the hiring organization proves that: (A) that the employee is free from the control and instructions of the employer (in the context of the quality of work) - both under the contract for the performance of such work, and in fact; (B) that the employee performs work that goes beyond the core business of the contracting organization; © that the employee has his own business or main job in the same field as the work that he performs for the hiring organization.

Does the new law work with Uber? The answer is not so simple. First, Uber really gives drivers (who use their equipment) a flexible schedule. Yes, there are rules that they must follow at work, but the previous factor is more important. In addition, drivers usually work for several companies at once. The need to compete for a presence on the platform (we will talk more about this later) is one of the main reasons why Uber is so unprofitable for the driver. This puts point (B) in question. If Uber is engaged in the transport business, then drivers are considered workers. Although the company claims that it only "serves as a technological platform for various types of digital trading platforms."

These words are not meaningless. For example, consider a commission: from the point of view of Uber, a company does not set a commission - it is a market clearing price that maximizes the amount of income earned by drivers. The idea is that if drivers could dictate prices themselves (and they cannot, therefore they cannot be considered independent contractors), then they would bargain with passengers until they agreed on the final cost. Over time, the cost of travel for all drivers and users should be equal. Uber insists that the company helps to get the equilibrium price faster and allows the market to exist, because otherwise the level of coordination necessary to achieve the market price would be impossible.

At the same time, such arguments, correct from the point of view of economic modeling, suffer from the lack of most economic models: they do not take into account the human factor. In this case, the drawback is not in the conclusion that the model leads, but in its manifestation: according to the company itself, “for consumers, drivers are the face of Uber” (quote from the Uber document for IPO). In addition, without drivers, Uber will not generate revenue. Of course, they can come and go when they want, and at the same time work for competitors. But on the part of Uber, it’s at least strange to say that drivers do not play a key role in the company’s business.

That is why the best solution to the classification issue is to accept that none of the old categories fits.

Uber drivers are not employees and are not contractors at the same time. It would be much more correct to define this category in the law in a new way, giving its representatives their own tax and social conditions that better match the previously non-existent model of their cooperation with the company.

What is Uber?

This is not a taxi company. Technological? Formally, yes, and here's why:

- The company has a software ecosystem of drivers and passengers.

- Like Airbnb, Uber reports low marginal costs, but travel analysis shows that the company pays drivers about 80 percent of total revenue — far from the lowest cost.

- The Uber platform is evolving.

- Uber is able to provide services worldwide.

- Thanks to the self-service model, Uber can make deals with anyone.

In the Uber model, the main problem is hidden in transaction costs: to attract and retain drivers on the platform is not cheap. This does not mean that Uber is not a technology company, but it emphasizes the extent to which its model depends on real-world factors. The problem is that Uber has no analogues in the offline world.

The magical market described above, in which Uber simulates countless face-to-face negotiations between drivers and passengers (which would reach a market price with an infinite amount of time and with an endless supply of patience), is largely technological. This market uses modern innovative technologies (smartphones and cloud computing) and is software in itself, which means it brings almost infinite profit and is constantly being improved.

Uber's financials reflect the following: last quarter, the company's gross margin was 51%. This is slightly lower than the gross margin of a typical SaaS company (70% and higher), but only because of insurance, which scales linearly with revenue. The software behind the Uber marketplace scales very well.

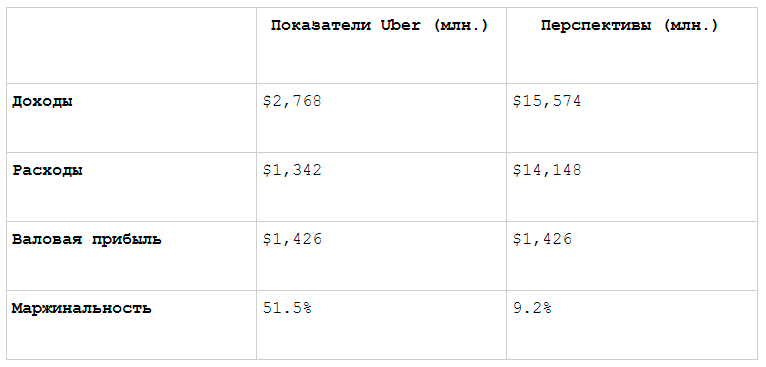

But the problem is that financial indicators give an incomplete picture of the experience of Uber, since users pay not only the service, but also the drivers. Therefore, when studying financial indicators of Uber from the point of view of a passenger, the situation looks much worse. Consider the results for the last quarter:

Suddenly, this gross margin ceases to be similar to the performance of a software company. Keep in mind that this is all that Uber receives without deducting fixed costs. The only way for such a company to remain viable is to grow to a truly gigantic size so that it has sufficient gross margin to cover fixed costs. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find new customers every day. The costs of sales and marketing only increase the height of the mountain that you need to climb!

It does not follow that Uber is not viable: all of Gurley’s arguments about the general addressable market and the ability of the service to dominate it are still applicable thanks to technology. Uber is not a taxi company! At the same time, judging by its history in the market, a different valuation method, different from those usually applied to technology companies, was also quite appropriate. In other words, a company does not fall into any definition.

Anomaly Uber

While technology companies are characterized by zero marginal cost, increased returns to scale and ecosystems, venture capital firms resemble equity financing (which indicates a limited downside and infinite growth potential) and are associated with a risky approach to portfolio management focused on high returns .

That is how venture capitalists approached Uber in 2017. At that time, his largest investor was the investment company Gurley Benchmark. It was she who insisted on the dismissal of former Uber CEO Travis Kalanik, and then sued him. Throughout their careers, the venture capitalist has invested in dozens, if not hundreds, of companies, while most founders found only one startup. Of course, the venture capitalist can gain short-term benefits by firing the founder or refusing to subsidize the company at the wrong time for her, but in the long run it is not worth it. Rumors fly fast, so the number of successful venture capitalist deals depends on their reputation.

The whole point of venture capital investment is to find a startup that can reach its full potential. The losses of the venture capitalist are always limited by the size of their investments (in addition to the time spent and opportunity costs). At the same time, these investments can bring multiple returns. That is why most venture capitalists try to remain, as they say in Silicon Valley, “cute” and “friendly to the founders.”

In the case of Uber, however, everything turned out differently. Uber’s latest valuation of $ 68.5 billion is almost equal to the total value of all successful startups funded by Benchmark since 2007. Of course, Uber is of particular importance to the investment company. Surely these figures were guided by Benchmark, putting forward a lawsuit. Does this worsen the reputation of the company, potentially depriving it of the opportunity to finance a new Facebook? Undoubtedly. However, Uber's sheer scale and potential profit make it clear that Benchmark should no longer take risks. Now her task is not to finance the new Facebook, but to guarantee her share of profit from investments already made. This estimate turned out to be erroneous. At the same time, $ 53.2 billion is also a huge amount, and Benchmark would probably not have changed their minds. It was then that SoftBank entered the business.

Vision fund

Softbank CEO and main driving force behind the Vision Fund, Masayoshi Song, said in an interview with Bloomberg a year ago that he wanted to "play big." SoftBank's big bet on WeWork symbolizes the general approach of Son. Asked about his investment style, he told Bloomberg last year in an interview that other venture capitalists tend to think too shallowly. Its purpose is to change the course of history, supporting companies that can change the world in the long run. It requires these companies high costs in areas such as attracting customers, hiring talented specialists for research and development, and, as he recognized, such spending tactics sometimes lead to conflicts with other investors.

“Other shareholders are trying to create clean, polished small companies,” said Son. “I always say:“ Let's act rudely. We do not need polishing. We don’t need efficiency right now. Let's play big and win big victories. ” The "other shareholders" that Son makes fun of are trying to create technology companies: prepaid fixed costs for developing software with a high gross margin from its sale. These are those companies that require investors with a desire for justice, a willingness to take risks and decency.

All these qualities do not apply to the Vision Fund. She does not seek justice, but privileged capital - so she guarantees that she will receive profit in the first place. Moreover, the fund not only seeks to invest in better companies, but is also ready to use its capital to develop less successful startups, forcing competing companies to unite. Vision Fund is ready to do everything possible to conquer the markets in which it invests, including getting rid of founders who are starting to bring problems to the fund.

The problem, however, is that the head of the Vision Fund could confuse “great capital needs” with “great opportunities”. The portfolio of the company impresses with a low number of “technology companies”. Almost everyone falls into the category of "neither one nor the other," which is defined by Uber. Entire categories (such as real estate and logistics) are characterized by interactions with the real world and almost all companies in the consumer category use technology to provide services for the real world. Another large category, fintech, by definition, needs huge amounts of capital. Most of these companies have attractive financial reporting indicators, but from the point of view of total revenue they bring extremely low gross profit (relative to technology companies) and have very high marginal costs.

Softbank must wonder about how many other markets are the size of a transport one in which a holding company can grab a fairly large chunk. For example, Vision Fund invested in OpenDoor, a startup that operates in a market that is larger than transport (residential real estate), but the potential transaction volume is much smaller. Zillow, which ranks second after OpenDoor in this market, has a market capitalization of just $ 6 billion, partly due to investor skepticism about margin.

This is the problem of the Vision Fund: yes, these companies have huge capital needs, and yes, the only way to succeed is to make them so large that their small margins begin to cover fixed costs. However, does it really guarantee big profits, or did Masayoshi Song make a mistake? It is not clear how many mistakes the Vision Fund can still afford: the Wall Street Journal previously reported that the fund promised 7% profit per year for 40% of its investors. This means that SoftBank does not have the opportunity to wait long for large profits, especially if WeWork starts pulling the entire fund down.

Worse, one cannot determine how many truly successful startups have Softbank. Of the 29 IPOs in the United States since the beginning of 2018, 20 have increased market capitalization compared to the offer price, and all of them are purely high-margin technology companies. Of the nine startups that have lost in price, four are trading companies, two are equipment suppliers, and only three are pure technology companies. Dream, however, views the latter as “clean, polished small companies” that are not big enough for the Vision Fund.

Vision Fund cannot be called a venture capital firm. At the same time, it is not a hedge fund focused on the public market. Vision Fund does not fall into any category, but it is not yet clear whether this will play to its advantage.

Good lessons

This story brings good news to the entire global technological ecosystem: the founders still have enormous opportunities to create a “technology company” (especially in the corporate environment), and the Vision Fund will not be an obstacle for them. Yes, there are fewer of them in the consumer environment, but these are rather the consequences of the dominance of large companies, not related to venture funds.

This is also positive for investors in the public market: despite the negative news about Uber and WeWork in the press, most companies grow after the IPO, and do not lose in price, and revenue as a percentage significantly exceeds losses. The technology company's success formula is still working.

It also means that analysts and investors should not have been afraid of WeWork. Those who investigated their growth potentials made a hasty conclusion and did not invest in the project, as they miscalculated while studying the margin.

And the most important lesson: in the future, you should be more skeptical of other technology startups that interact with the real world. The same applies to launching your own projects if you are still in search of an idea. It cannot be argued that this category is not viable. In addition, technology really sets these startups apart from existing companies. However, they may not always be called technological, and their future is vague due to scaling problems.

Based on

article material