The problem is not in the cognitive load due to multitasking, but in peripheral vision.

The problem is not in the cognitive load due to multitasking, but in peripheral vision.According to a

new MIT study , the key to staying focused on driving is simple:

keep an eye on the road and see where you are going . This may seem terribly obvious, given that “look where you are going” is one of the first lessons we learn when we start driving. But this new study focused on a slightly more complex question: is the problem with abstract driving one of the attempts to focus on two separate tasks at the same time, or could it be a question of where your gaze is directed?

When I learned to drive a car in the early 1990s, being distracted while driving was not a problem. After the proliferation of mobile phones, and then smartphones, drivers began to

increasingly correspond at the wheel . Not that the automotive and technology industries were unaware of this problem. Almost every new car sold today provides the driver with the opportunity to connect his phone to make phone calls using the speakerphone. Apple CarPlay, Android Auto, and MirrorLink all exist to transfer certain applications from a smartphone to the car’s infotainment screen.

In addition, new cars are increasingly equipped with modern driver assistance systems (ADAS), which will warn the driver about possible collisions or that the car is getting off the lane on the road. Unfortunately, none of this seems to make much difference. People

still use their mobile phones when they are driving, even if

they don’t know that it’s bad .

Where our eyes look or what our brain thinks

To test whether the problem is what we are thinking about, the authors of a study led by MIT postdoc Benjamin Wolfe developed the following experiment. Volunteers watched videos simulating a first-person view of a car driving along Boston, i.e., actually driving this car along these roads.

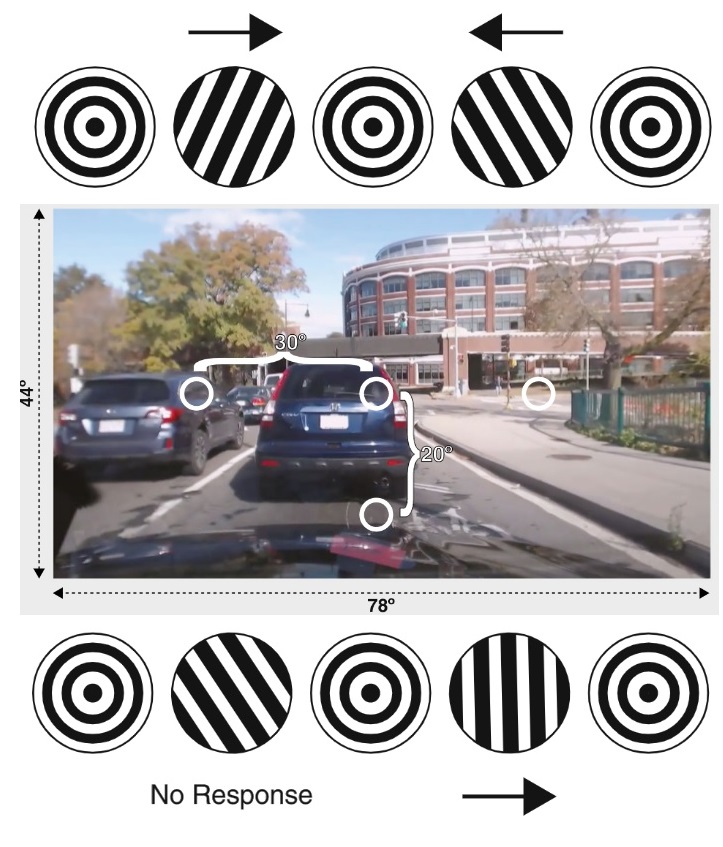

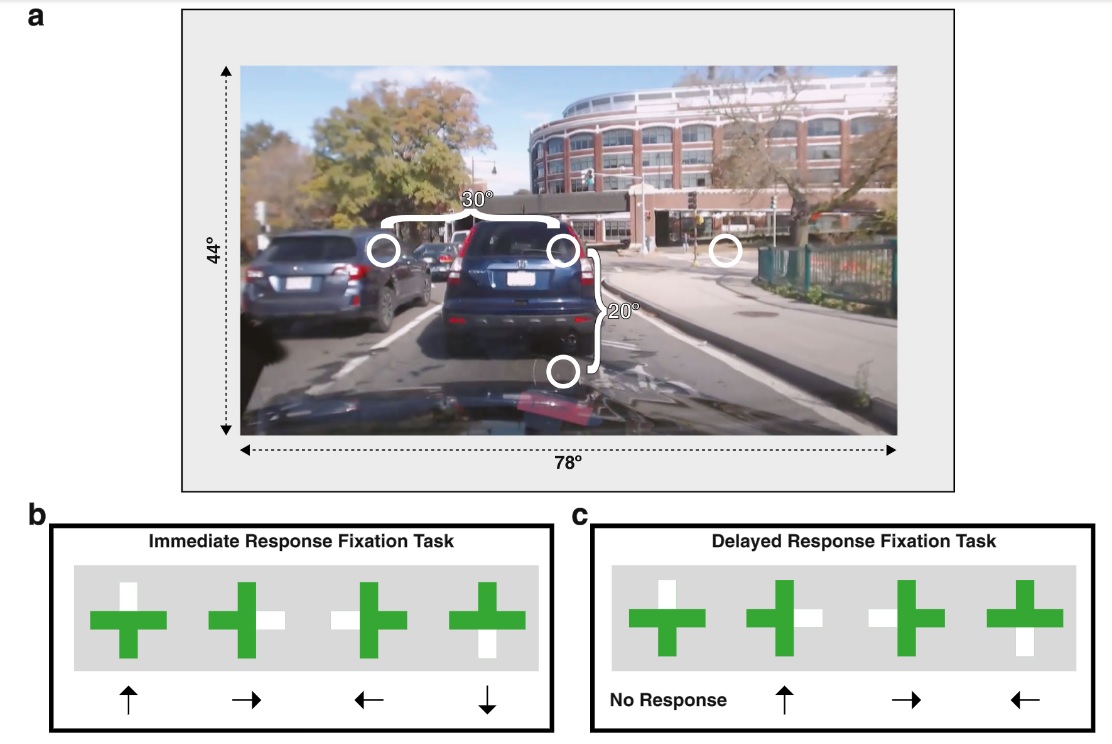

a) Angular distances. The right and left circles are separated by 30 °, the lower circle (smartphone) - by 20 ° b) Test for immediate reaction. Participants had to indicate on which side the color of the cross ray changed as soon as they noticed it by clicking the corresponding arrow. c) Test for deferred reaction. As soon as the first change in the cross ray occurs, it must be ignored, and as soon as the next change occurs, click on the arrow corresponding to the previous change.

a) Angular distances. The right and left circles are separated by 30 °, the lower circle (smartphone) - by 20 ° b) Test for immediate reaction. Participants had to indicate on which side the color of the cross ray changed as soon as they noticed it by clicking the corresponding arrow. c) Test for deferred reaction. As soon as the first change in the cross ray occurs, it must be ignored, and as soon as the next change occurs, click on the arrow corresponding to the previous change.For the first set of tests, each participant was asked to look at different parts of the image - right in front, 30˚ from each side or 20˚ below the center - during short video playback. Observing each necessary place on the screen, they should indicate whether the braking indicator on the vehicle in front is lit (by pressing the space bar on the keyboard).

In the second series of trials, participants were again asked to indicate whether they had seen the brake lights in the front lane, but with a slight complication. This time they were told to look at the green cross placed on different parts of the screen while playing the clips. In some tests, they were supposed to indicate whether one of the lines of the cross became white with the corresponding arrow key. In other tests, they had to keep an eye on whether the line of the cross had turned white, but only to show that after the next time it happened, various instructions allowed Wolfe and his colleagues to check both the immediate and the delayed reactions.

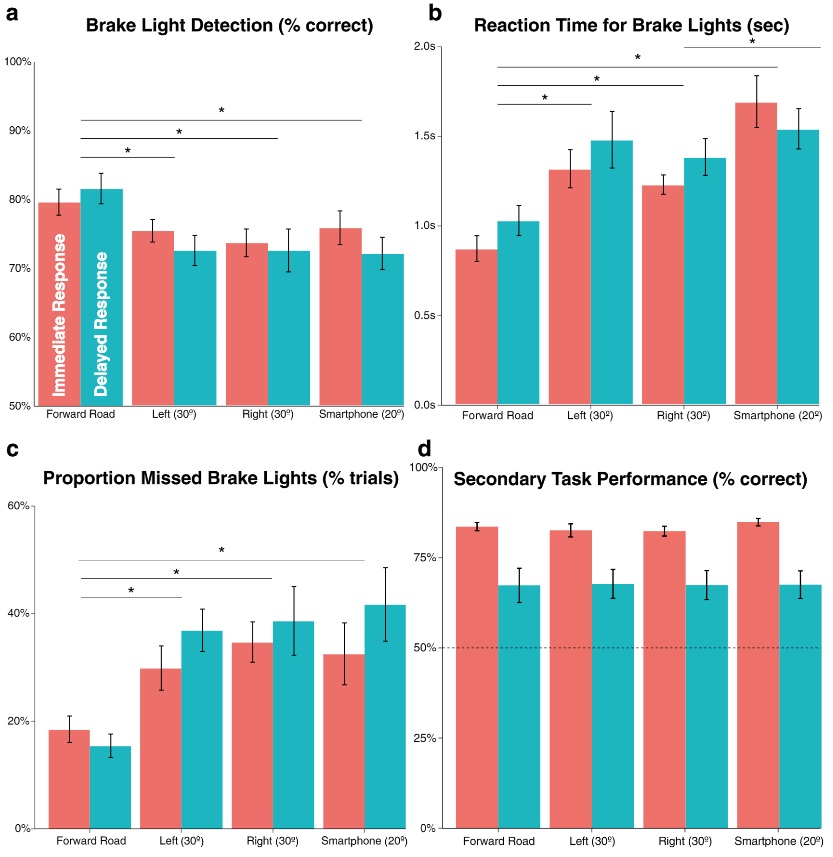

If the main problem with distracted driving is the cognitive workload, we expect participants to perform the first set of tests better and worse, tests with the highest cognitive load (delayed response to green cross changes). However, this is actually not the case.

Where participants were asked to watch was the main factor affecting the accuracy of stoplights; this was also the main factor affecting the reaction time.

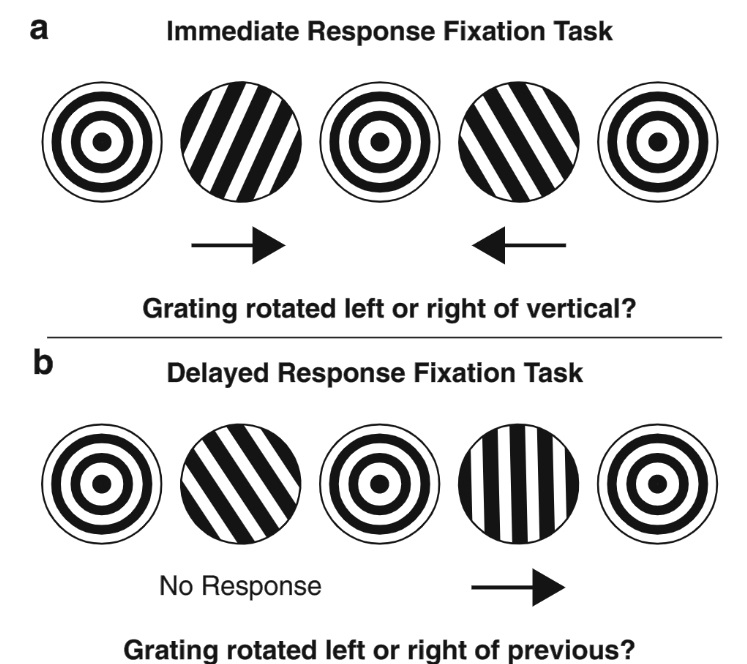

Participants performed best when they looked at the center of the roadway, and worst of all when they looked below the center of the screen.To make sure they really found something, the researchers conducted a third set of tests for a new group of participants. The first priority was to detect the brake lights in the forward lane, looking at certain areas of the screen. But this time there was another secondary task: to determine whether the figure rotated clockwise or counterclockwise, immediately or after the next change of rotation.

The subjects had to determine where the lines are inclined (to the right, left, vertically). The second time it was necessary to press the arrows with a delay of 1 clock.

The subjects had to determine where the lines are inclined (to the right, left, vertically). The second time it was necessary to press the arrows with a delay of 1 clock.We respond slowly to what is happening in our peripheral vision.

Again, the main factor both in detecting the stop signal and in response time was where the participants were asked to look. The best indicator was achieved when they were told to look at the center of the screen, and the worst - 20 ° below the center of the screen. Meanwhile, the effect of increasing cognitive load on reaction time was modest. Viewing a screen area other than the center increased the reaction time by an average of 458 milliseconds. But higher cognitive loads contributed to an increase in response time of only 35 ms.

“We are not saying that the details of what you do on the phone cannot be a problem. But when delimiting tasks and shifting gears, we showed that distraction from the road is actually a more serious problem, ”says Wulf. “If you look down at your phone in a car, you may know that there are other cars around. But you most likely will not be able to distinguish a car from that which is in your lane or near you. "

This is certainly an intriguing set of conclusions, and “keep an eye on the road ahead” remains good advice for anyone who drives. But people often ignore useful tips, which means that we will inevitably be offered technological solutions.

This study, of course, is a strong argument in favor of head-up displays in cars, although perhaps they also need to be kept relatively simple. There is evidence that

mixed visual attention also increases distraction . When it comes to placing infotainment screens, think of the

Mazda 3 or

Tesla Model 3 , which sets the display as close to the driver’s line of sight as possible, even if it means no touch screen interfaces. In fact, perhaps we should avoid full viewing of infotainment screens with more advanced voice commands in automobiles, and this

industry trend is already gaining momentum . In any case, the results of the study are further evidence that effective monitoring systems should include

eye tracking or

face recognition , because simply a sensor on the steering wheel is not enough.

About ITELMAWe are a large

automotive component company. The company employs about 2,500 employees, including 650 engineers.

We are perhaps the most powerful competence center in Russia for the development of automotive electronics in Russia. Now we are actively growing and we have opened many vacancies (about 30, including in the regions), such as a software engineer, design engineer, lead development engineer (DSP programmer), etc.

We have many interesting challenges from automakers and concerns driving the industry. If you want to grow as a specialist and learn from the best, we will be glad to see you in our team. We are also ready to share expertise, the most important thing that happens in automotive. Ask us any questions, we will answer, we will discuss.

Read more useful articles: